This post is part of an ongoing series highlighting modern and historical craftivists who inspire action through creativity.

This week’s craftivism story is really sticking with me and inspiring me, and I hope it does the same for you. It’s about the Changi Quilts from WWII—a quiet but powerful act of resistance and hope, stitched by women who were imprisoned in Singapore.

When Singapore fell to Japanese forces in 1942, civilians associated with the colonial administrations—teachers, doctors, nurses, nuns, missionaries, and their families from countries like Britain, Denmark, Australia, and Canada—were taken as prisoners. Men were sent to one camp, and women and children to another, with no way of knowing if their loved ones were even alive.

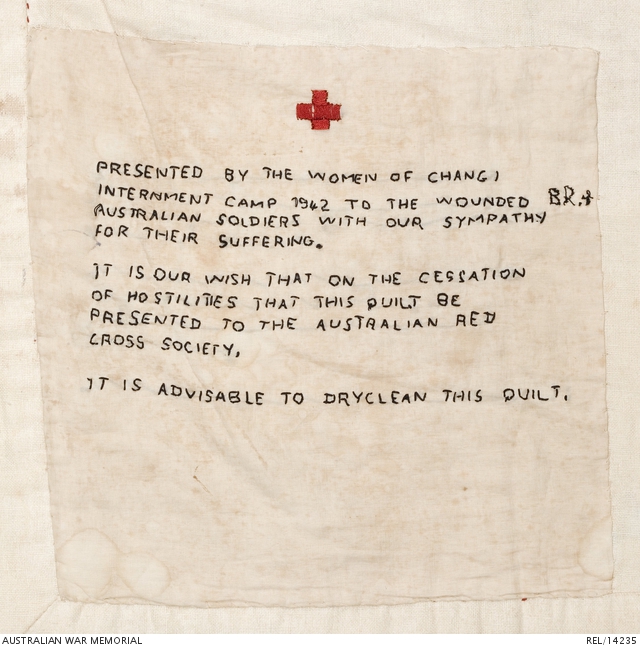

Amid this uncertainty, one prisoner, Ethel Mulvaney, a Canadian volunteer with the Australian Red Cross, had an idea: the women could make quilts for the men’s hospital ward. But more than just blankets, these quilts could carry messages—proof that their wives and children had survived.

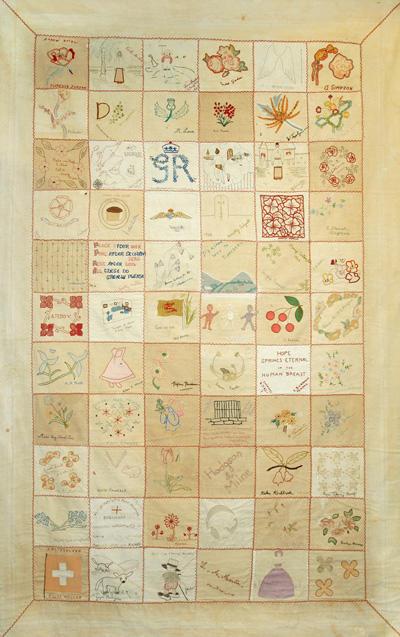

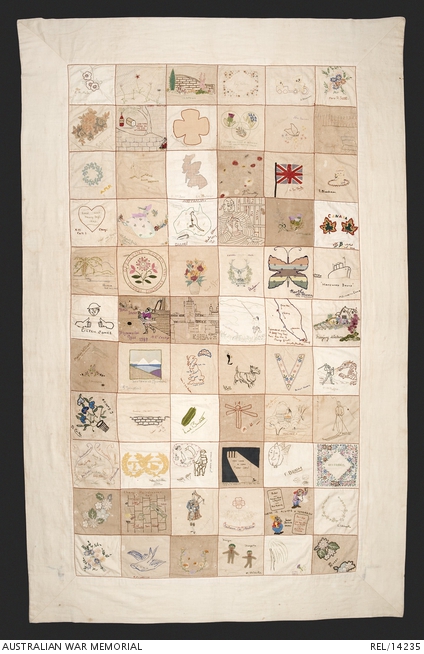

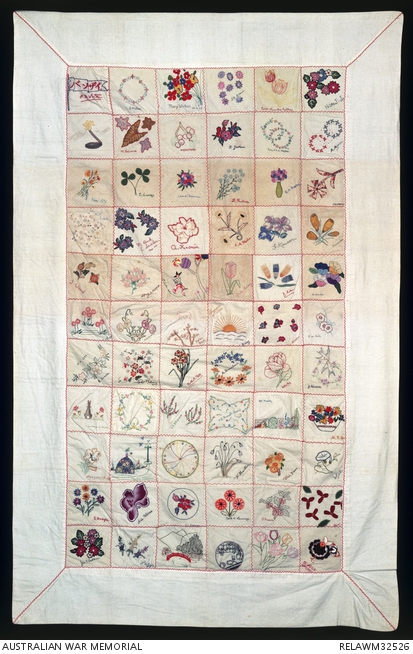

Mulvaney coordinated the effort. Each woman was given a 6” square to embroider with her name and a personal symbol—something that represented her identity. These squares were stitched into three quilts, each with 66 panels:

- One for British prisoners

- One for Australian prisoners

- One for the Japanese sick bay

It’s believed that the inclusion of a quilt for the Japanese helped secure permission to send the others to the men’s camps.

🧱 The Purpose Behind the Quilts

These quilts served three key purposes:

1. Communication

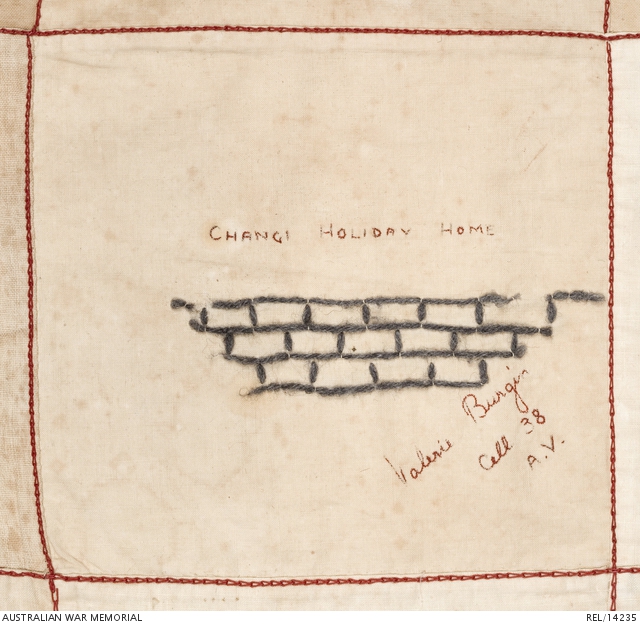

Direct communication between the men’s and women’s camps was forbidden. But by placing these quilts in the men’s sick bays, the women found a loophole. Each square carried names, symbols, patriotic emblems, and even coded messages. One square reportedly let a father know that his wife had given birth to a son.

2. Morale & Mental Focus

Creating the quilts gave the women a purpose and a way to cope with the monotony and trauma of imprisonment. It also fostered a sense of community—an essential survival tool in a dehumanizing environment. As I’ve explored in other posts, crafting can be a powerful tool for managing stress and creating connection.

3. Preserving Identity

Prison camps are designed to erase individuality, but these embroidered names and symbols were acts of quiet defiance. They affirmed each woman’s identity, her story, and her ties to home.

🧵 Resourcefulness in Action

The Changi Quilts also showcase incredible resourcefulness. The women scavenged what materials they could—old sheets, rice sacks, and threads pulled from unravelled garments or hems. Every stitch was made under conditions of scarcity and surveillance, adding layers of courage to their creation.

📍 Where Are the Changi Quilts Now?

Amazingly, these quilts survived the war and can still be seen today:

- The British Quilt is housed at the British Red Cross Museum and Archives in London.

Source: British Red Cross Museum & Archives - The Australian and Japanese Quilts are on display at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

🔗 Learn More

If this story speaks to you, I encourage you to read more here:

- Changi Quilt – Secrets and Survival (Red Cross UK)

- The Changi Quilts – Dutch Australian Cultural Centre

- The Iconic Changi Quilts – Australian War Memorial

Leave a comment